By Sarah White

There was a time when “layout” was considered a skill and I was adept at it. Then innovation ate my craft.

As a layout artist, I could take someone’s images and words and make them into camera-ready artwork for printing. I pasted black-and-white components onto artboards, and then neatly printed my instructions on tissue overlays for unknown craftsmen to follow. They made printing plates from my artboards, then inked sheets of paper in just the places I intended and no other. Those sheets would be bound and finished into brochures or annual reports or posters or album covers or any kind of commercial communication, what the advertising trade calls “print collateral.” That was my domain, my realm, the body of knowledge I had carefully assembled. I was one of the fastest, neatest, and best.

My training began in the composition room of the “Indiana Daily Student” in Bloomington, Indiana in the fall of 1974. I reported to work in the late afternoon to help put out the next morning’s paper. The printing trade, which had changed remarkably little since the innovation of the Gutenberg Press in the 1540s, was at that time in the throes of transition from hot lead type to photo-composition. I was part of the new wave. My job was to set columns of body type on a glorified typewriter with magnetic cards for memory, and set headlines on a Compugraphic IV that required me to load different filmstrips for each font, then tap my words into a keyboard while watching a 60-character display scroll by. I ran cassettes of exposed paper through a chemical processor and hung the strips of headlines up to dry. There was no “WISIWIG” monitor and no desire for it.

When all the typing was done (I say typing to distinguish what we female clerical workers did from what the unionized male typesetters we replaced had done), I would leave my machines and help the paste-up people make up the newspaper pages. We’d coat the back of our galleys of type with soft wax, set them precisely on gridded white artboards, and burnish them firmly into place, ready for the printer’s copy camera that would turn them into negatives and subsequently, aluminum printing plates.

The night editor stood by to re-write a line if a story failed to fit. The proofreader scanned the flats for errors, for which I would typeset two-line corrections and, using the sharpest X-ACTO knife to hand, slice out the bad lines and mortise in the patches. Finally, the man smoking in the corner would box the artboards and drive them to a printer. It might be 9pm, or midnight.

This was a perfect after-school job for a student and I kept it for most of my college years. I enjoyed turning a pile of copy and photos into camera-ready copy, and it paid better than other kinds of clerical work. After graduation, I brought those skills to ad agencies where pasting up pages eventually led to designing them.

Paste-up as a craft was like carpentry but for girls. You had similar questions of construction, of procuring and cutting materials. You adhered to the same aesthetic of doing a job precisely, of getting each assembly right so that in the end, the entire structure is true, square, and beautiful.

And then there was the parallel craft, more artistic but just as precise, of creating designs for pages by making “comps,” shorthand for “comprehensive renderings.” We used magic markers to convey the impression of the page for client review, ruling neat columns of horizontal lines to indicate body text and hand-lettering type to mimic headline fonts to come. Sketchy color renderings showed what photos might look like. If one developed a charming style of “comping” one’s ideas sold better, so I pursued this craft just as assiduously as my paste-up.

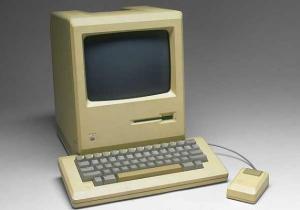

In 1984 I became a partner in a graphic arts studio called Abraxas. That same August, the first Macintosh was introduced at COMDEX. The innovation that would eat my layout skills for lunch was just ordering breakfast.

The next year we bought a PC desktop computer for the fiscal side of our business, and a year after that layout artists began to whisper to one another that it was possible to set type from a personal computer using Pagemaker. Before long I bought a Mac and I began trying to maintain the typesetting trade’s exacting standards while working in early, buggy, software.

I became increasingly grumpy. Something fundamentally satisfying in my work was disappearing. More of the layout artists’ skills were sucked from the physical world into that vacuum on the other side of the computer screen. Last to go were the technical terms: “cut” and “paste” were reduced to metaphors.

Finally in 1993 I began transferring finished pages from my computer over the phone to the printer, instead of cabbing a stack of artboards across town. Innovation wiped the last crumbs of my craft from its lips and belched.

Then one day in 2005 I visited a Scrapbook Expo. When I walked into that exhibition hall full of craft supplies, I felt a shock of recognition and a tug of angry sorrow. Here were the colored markers, the X-ACTO knives, the self-healing cutting mats. Here were all my art supplies, my carpentry for girls, my lost craft.

These people were playing at being art directors, book designers, graphic artists. What we clerical workers had made decent money doing, what the type compositors and pre-press negative strippers had made solid blue-collar careers of, these scrapbookers were now pursuing as a hobby. I wandered that Expo feeling like dinosaur bones trapped in a sedimentary layer, one level up from the printing tradesmen.

By this time I had shifted to freelance writing, but I was still mourning the loss of the craft I had taken such pride in. It could seem small of me to resent the scrapbookers for enjoying in their playtime something I used to do for pay, but that’s how much it hurt to be reminded of all the computers had stolen.

Now, I’m having the last, sour laugh. Digital photography has eaten the scrapbookers for supper. Creative Memories and Archivers, the two leading players in the scrapbooking industry, were both defunct by the end of 2014.

I met my friend Jesse Kaysen back in those halcyon layout artist days. It’s her observation, not mine, that Gutenberg et al provided the foundations for a very different human race. Literacy—the power of words, printed and distributed—changed our relationship to God, to the law, to ourselves. Yes, there were some innovations along the way, but linotype operators were basically doing what Gutenberg did, just louder and faster.

The onset of phototypesetting ripped those traditions away from their historic context. Not only have the workers lost their jobs; the unions have lost their workers, and the middle class has lost its unions. The printed word has lost the silent guardians, the typesetters, who have been quietly ensuring legibility for hundreds of years. These are the things we dinosaurs talk about as we molder in our sedimentary layer.

We are still grumpy that innovation ate our craft. But if innovation teaches us anything, it is that where there’s a need, someone will come along to fill it. Something about layout was fundamentally satisfying enough that scrapbookers did it for fun. Who will be next to wax and cut and paste, and will it be for fun or for money?

With all the disruptive innovation in the publishing industry, I find it entirely believable that somewhere, a Luddite DIY squad is right now preparing to return the layout craft to the physical world, to revel again in the unique sensuality of T-square, X-ACTO knife, and wax. Maybe I should start a movement.

Great essay. I just sat in an presentation from a couple of hotshot digital artists who are making their media look like zines.

LikeLike

You have given me lovely, specific details to use to describe my newspaper “typesetting” jobs in the 1970s. (And I had the same reaction when I first encountered scrapbookers in the 2000s.)

LikeLike

A wonderful reminiscence, Sarah, of the days when it took a “real woman” to produce printed material.

LikeLike

Sarah, I remember the talented legions of layout artists and graphic designers as a screen-printer during the mid-1970s until the mid-1990s when I was a printing sales rep, and later a print buyer and production manager. My favorite part of my job was working with designers and production artists as they handed off art boards to me with rubylith color separations or vellum overlays colored with Pantone markers. These were true artisans and craftspeople. As a printer and later a print buyer, I also enjoyed the press checks, spending long hours watching master printers start up the web and litho presses and ensure that color and registration was right on and to spec referencing color proofs.. I’ve always loved the smell of ink and the sounds of the presses running. Though digital tools consumed less materials and often sped up the process, some of the artistry was lost. Your post brought all that back for me. I enjoyed the journey.

LikeLike

Well told, indeed, Sarah! You’ve achieved a nice combination of personal story and social/technological history here. I’m thinking that yes, the digital revolution taketh away, but so does it giveth. Your craft was eaten; yet people all over the world can now communicate directly and freely (or freely in most places). Just nowhere near as beautifully. 🙂

LikeLike

Fascinating commentary Sarah. I have a new appreciation of your earlier career skills and admire your transitions along the way. You are amazing!

LikeLike