By Marlene Samuels

We’d read every book— about the experience, recovery, getting organized—plus had watched numerous documentaries. Four weeks before our life-changing event of becoming parents, our obstetrician encouraged us to register for Lamaze class taught by Nurse Practitioner Maureen McDougal, Chicago’s ultimate authority.

I was beginning my last trimester. Larry, my husband, and I were at least ten years older than every couple in the class except Maria and Enrico. The four of us hit it off immediately that first meeting. A May-December marriage, Enrico presented as an elegant gentleman. A successful architect from Italy, he was eighteen years Maria’s senior. He arrived to classes attired in his interpretation of casual: gray flannel slacks, cashmere blazer, silk shirt, ascot at his neck. We marveled that he felt comfortable for sitting on a floor mat to support Maria during our exercises.

“Quickly, take your places, everyone!” Ordered Nurse Maureen, our distinguished instructor. She clapped her hands loudly as though calling kindergartners to order, one of her numerous annoying habits. “Folks, we’re on a schedule. Your babies aren’t!”

“Gentlemen, be seated on your mats, cradling your partner’s head in your lap. Remember, your job is to ensure her comfort!” We scrambled into position for our first exercise. Women awkwardly lowered themselves. “Men, no whining about leg cramps! Tough it out. You’re not the ones giving birth.” As we assumed our positions, Maureen shouted more commands.

“Okay, time for breathing practice. I must have undivided attention.” Everyone nodded. “First, we’ll exhale fully before deep breathing. Ready? Exhale! Now deep inhale! Hold for ten now, exhale slowly.” Maureen possessed the finesse of an army drill sergeant. By the end of our first class, she’d earned the moniker, “Lamaze Nazi.”

During week two, Maureen issued her three-minute warning to get into position. We’d barely returned to our mats following a fifteen-minute break when Maureen and my husband engaged in a stare-down, a death-glare really. He’d joked about focal-point exercises with Maria and Enrico, “I’ll bet Lamaze-breathing is like aspirin.” He whispered too loudly. “It works, but you have to believe.” They burst out laughing, actually guffawing. Larry inadvertently made eye contact with Maureen, who was hardly amused.

Sunday Lamaze classes became our weekly foursome ritual. After class, we’d go out for lunch. By our last session, Maria was too exhausted to eat out, and I focused only on changing into my Hawaiian muumuu. We had zero interest in food or socializing. “You’re due next week, right?” Asked Maria as we bid one another goodbye and good luck.

“How’d you remember?” I asked. “And you?”

“Two weeks, three days, but who’s counting? I have a great idea! Let’s have a reunion dinner at the end of June. We each should have had our babies, and we’ll be more than ready for adult company. Interested?” An ex-fitness trainer, Maria was that pregnant woman other pregnant women resented because, from any view but sideways, she didn’t look pregnant. I feared she’d be reunion-ready well before I was.

The last Friday of June, my phone rang. I grabbed it, my shrieking newborn flat against my chest. “Hey, Marlene,” the familiar voice said, “it’s Maria. Remember me?”“How couldn’t I?”

“So, whad’ya have?” She asked.

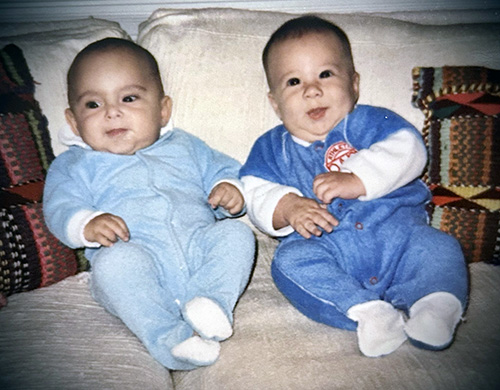

“A boy, three weeks ago. You?”

“Same, two weeks ago. You up for getting out yet? My mom’s helping with Giancarlo so I’m actually getting some sleep.”

“I’d love to, but honestly, I’m not ready to leave David with anyone.”

“Of course you aren’t. So I’ll cook dinner, and you’ll all come over!” She sounded like a peppy, excited schoolgirl. “We have a porta-crib, so we’ll put the babies to sleep in the same room. My mother’s in our guest room next to the nursery. She insists she’ll take care of them.”

“Wow, that sounds fantastic!” I could hardly believe her invitation.

“Does next Friday, six-thirty-ish work?”

I hung up the phone with a new understanding of cabin fever. The prospect of socializing underscored that it would be the first time in months I’d wear clothes not designed by Omar-the-Tent-Maker.

We parked in their building’s garage. Nervously, I lifted our newborn from his car seat while Larry emptied our trunk of enough gear for a month abroad. We entered the lobby. The doorman called our friends, announcing our arrival. “I’ll key in their floor for you.” He said, holding the elevator doors. “You’re going to the penthouse.”

The elevator doors opened directly into their apartment. Elegantly dressed, Maria and Enrico were waiting. The instant Maria saw us, she giggled, “Hey, we’re grown-ups again!”

Their stark white living room’s ultra-contemporary furniture was a contradiction to Enrico’s reserved appearance. Touring the apartment, we admired the skyline from their penthouse. Simultaneously, we realized it was time to ready our newborns for bed. Remarkably, both fell asleep immediately, and we repaired to the living room for cocktails and hors d’oeuvres. Next, Maria directed us into a narrow dining room where a massive black granite slab supported on six concrete pillars served as their dining-table.

“Marlene, sit there.” She said, pointing to the end of the table. “It’s the best view of Chicago at night.” I was mesmerized by the skyline from the fifty-fifth floor. We enjoyed a leisurely dinner, several wines, a pasta first course, Osso Buco, salad, then tiramisu. Next were cheeses and shots of Grappa. We laughed hysterically. We ate chocolates. We laughed some more. Maria proved an outstanding cook.

After weeks stuck home with less sleep than either Larry or I needed, our evening out was an excellent break, but by eleven o’clock we were exhausted. “It’s gotten so late!” Larry said, consulting his watch. “We need to get going.”

“Such a brilliant idea and fabulous evening!” I gushed to our friends. “Next time, our house.” Enrico pressed the elevator’s call button while we chatted away. The doors opened. We hugged and kissed, Italian style — cheek to cheek to cheek— agreeing to get together soon. Larry and I stepped into the elevator, totally relaxed, given the evening’s food and wine.

Suddenly, horror hijacked Maria’s face. The elevator doors were closing and she shrieked, “Oh my god, you can’t leave! You forgot your baby!”

©2026 Marlene Samuels

Marlene holds a Ph.D., from University of Chicago. A research sociologist by training, she writes creative non-fiction by preference. Currently, she is completing her book entitled Ask Mr. Hitler: A Memoir Told In Short Story. She is coauthor of The Seamstress: A Memoir of Survival, and author of When Digital Isn’t Real: Fact-Finding Off-Line for Serious Writers. Her essays and stories have been published widely in anthologies, journals, and online. (www.marlenesamuels.com)