By Marlene Samuels

In 1955, Polio raged through the densely populated Montreal neighborhood in which I was growing up. The vaccine hadn’t yet become available in our Canadian province even though it was already being administered in the United States. No surprise, then, that this horrible disease was sweeping through every congested city in Canada like floodwaters into sewer-drains.

For two months every summer during my childhood, my parents rented a shack of a cottage one-hundred and fifty miles north of Montreal in the Laurentian Mountains. Our family joined other Jewish immigrant families for the summer exodus out of the city into Quebec’s rural villages that were distant enough to accomplish one goal: get children out of the city during the season parents believed was peak for contracting every life-threatening disease known to humanity.

These villages were close enough for husbands to leave Montreal on Friday afternoons, arriving in time for Shabbat dinners and an abbreviated three-day weekend with their families. It was the middle of July. Dad had just driven back to Montreal the morning before. Mom, Jake and I sat at the kitchen’s formica table ready for dinner.

“I can’t eat, Mom,” my brother groaned. “I can’t turn my head and it hurts too much to swallow. I’m going to cry!” His eyes filled.

“Maybe you’re just over-tired?” My mother suggested. “You know, you’ve been pretty wild since we got up here, much more than you are in the city.” Jake nodded, unconvinced. “How about I’ll make you some warm milk with honey and you’ll get into bed early?” He nodded. Two huge tears rolled down his cheeks.

Morning arrived and with it, Jake’s intensified symptoms. “Mom, I can’t swallow at all! I can’t even turn my head and it hurts much worse than it did last night. And my back is also killing me now!” His sobs increased. “My neck and back feel like someone’s ramming a rod into them.” He howled trying to describe his symptoms. “Could it be tonsillitis?” He asked, hopefully.

“Stay here, both of you!” Ordered Mom. “Don’t you dare leave this house. I’m going to the pay-phone at Rechard’s Grocery to call Dr. Ostrovich in the city.” She grabbed her purse and took off jogging down the gravel driveway for the one-mile trip to Rechard’s pay-phone. When she returned, Mom was flushed, breathless and sweat-drenched. But ger voice was surprisingly calm as she relayed everything Dr. Ostrovich had told her.

“Dr. O said it sounds like symptoms of that Polio virus. He wants you back into the city immediately so he can see you. He also said that treating you right away,” she continued, “means decreasing the chance you develop any problems.” Those “problems,” we learned later on, were serious risks of paralysis.

Because Dad wouldn’t be back out for three more days, we had no car. But Mom wasted not one second at Rechard’s. She didn’t call Dad. Instead, after she’d spoken with Dr. Ostrovich, she called the village’s only taxi and it arrived at our cottage seconds after she did. “Children, put anything you’ll want at home into my bag now! I’ve checked the train schedule from Shawbridge to Montreal but the next one isn’t until six-o’clock tonight. We’re taking a taxi!”

Only when we’d settled into the taxi’s back seat did Jake and I comprehend that we weren’t heading home. “Children’s Memorial Hospital, please!” Commanded Mom to the French taxi-driver. Worried he couldn’t understood her Romanian accented English, she repeated herself loudly.

“Oui, oui Madam!” He snapped, as though insulted. Rolling hills and lush green fields blurred past. The driver, sensing Mom’s anxiety, drove like a lunatic.

Upon our arrival, Jake was admitted to the hospital and taken, immediately, to the pediatric isolation wing. During our pre-cell phone days, Dad was stunned when his boss appeared in front of him at 2:00 pm and told him to leave. The hospital’s director had called the factory where Dad worked and insisted they give the rest of the day off.

One wall of Jake’s room was glass beginning three feet above the floor all the way to the ceiling—the front of a fish-tank. We could see each other but were forbidden any in-person contact. Mom, Dad and I visited daily through a glass wall. The mandatory barrier upset my parents but provided endless amusements for Jake and me. We pantomimed, mashed our faces against the glass and conducted games of charades.

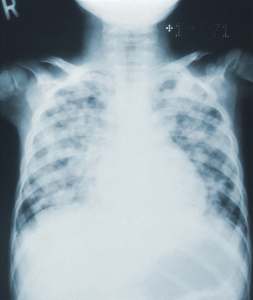

Three days after he’d been placed into isolation, my brother developed breathing problems. His doctor raced into our part of the room and led us into the hallway.

In a near-whisper, he said, “I’m glad you were already here. Your son is experiencing serious breathing issues so the Polio team wants him to go into an iron lung for a few days. It should minimize stress on his chest and that can help his recovery.” He explained, then added, “He’s a lucky boy! His Polio is a milder strain than what we’ve seen so far!”

By the end of the second week we were back in the city, Jake was still at Children’s Memorial. His three best friends noticed our lights were on and rang the door-bell. “Hey, so what’s with Jake?” Asked Itsick Barsher.

“Is he really in the hospital?” Asked Franklin Feldman.

“Yeah, and why’s he there for so long, anyway?” Asked Melvin Mishkin.

“Yea he’s in the hospital. He’s supposed to stay for three weeks, maybe longer. Nobody knows.” I explained, feeling official.

“Why’s that?’ Itsick asked. “What are they doing to him?”

“He has to stay because he’s getting iron lungs.” I said.

“Yikes, iron lungs!” They exclaimed, simultaneously.

“What happens to his old ones? I mean, can he keep them if he gets iron ones?” Asked Franklin.

“Bet those iron ones are plenty heavy, huh!” Added Melvin.

“I didn’t even think about that when the doctor said Jake was getting iron ones. I’ll go ask my mother. For sure she’ll know!”

Afterword

Jake was released from the hospital at the end of his third week. Deemed non-contagious, his recovery was nothing short of miraculous although he did experience some slight paralysis of several toes. Considered temporary, he was prescribed physical therapy three times a week to expedite his recovery. This part of Jake’s polio proved entertaining for the two of us as well. Physical therapy consisted of lifting marbles with his toes. I was beyond excited to be included as a participant and upon arriving home after these sessions, we’d practice drawing with crayons held between our toes.

I received my Polio vaccine as soon as Jake was admitted to the hospital and he received his before being discharged. It wasn’t clear whether having Polio developed immunity to the disease. My brother recovered fully and has led a productive and extremely successful life except for one glitch in his story.

During the past two years — some sixty-plus years after the great epidemic, a significant number of those who’d recovered from juvenile Polio have begun to experience a range of very specific, painful symptoms.

Extensive testing has revealed a condition termed “post-Polio Syndrome.” All said, the long-term effects of viruses that lay dormant for most, if not all, of our lives, can and do reemerge unexpectedly— such as Chicken-pox and Shingles, Polio and post-Polio syndrome.

In an era when we possess the means to prevent so many horrible diseases, it’s beyond distressing that too many populations continue to question the value of inoculations.

© 2023 Marlene Samuels

Marlene holds a Ph.D., from University of Chicago. A research sociologist by training, she writes creative non-fiction by preference. Currently, she is completing her book entitled, Ask Mr. Hitler: A Memoir Told In Short Story. She is coauthor of The Seamstress: A Memoir of Survival, and author of When Digital Isn’t Real: Fact-Finding Off-Line for Serious Writers. Her essays and stories have been published widely in anthologies, journals, and online. (www.marlenesamuels.com)