By Faith Ellestad

In years past, far past, my husband used to refer to me, I assume affectionately, as Pollyanna. I was always in search of ways to make things better, or at least more cheerful. Yes, I looked on the bright side of life. If I could get a laugh or solve a problem, I had won the Oscar. I was relentless in my sunny outlook. God, I must have been insufferable.

The antidote for my joie de vivre was, predictably, adulthood. Kids, jobs, family crises. Sickness and health, poverty and sustainable income, better and worse, Good times and less excellent ones. As we drove our Volkswagen down the highway of life, Pollyanna was relegated to the back seat.

Then came Covid, long Covid, the deaths of my mother, brother, and dear friend, my dog and cats, and with the emotional struggles of those around me in addition to my own, I thought I had hit bottom. Yes, there were occasional visits with friends, and thankfully, “Spring Baking Championship” on HGTV, but my hold on sanity was tenuous, and pretty much dependent on Trump losing the election. (I understand not everyone feels the same, but this is a personal essay.). In any case, that obviously didn’t happen, and since then I have been staunchly glued to the news on TV and online, basically force-feeding my saddest, angriest, and most depressive instincts.

What might happen? Will Social Security go away? Will health insurance be curtailed? Will Medicare not cover the services we need? Will democracy survive? I’ll spare you every last droplet of my brain-ringing, but since many of you are in similar situations, or know someone who is, you get the idea.

Nights of lying awake spinning, days turning off the TV just to turn it on again a half-hour later. Trying not to talk constantly about politics, but everyone else is anyway, so get-togethers seem more like support group meetings.

After a particularly bleak couple of weeks, I decided I had to at least try to shake things up. What options might there be for improving one’s outlook? Exercise would have been a good choice, but I was recovering from spine surgery and emphatically curtailed from most physical activity including, unfortunately, exercising and fortunately, cleaning. I had no dog to walk and no snow to shovel (forbidden anyway). I didn’t have enough laundry to keep me occupied, even loading the washing machine one garment at a time, and the limply drooping houseplants were a testament to the dangers of boredom-induced over-watering.

I wasn’t just drowning my plants, I was underwater, too. There had to be something uplifting, somewhere. What, what, what? I racked my brain, and I probed my family’s brains. We all came up empty and the news only got worse. I stopped reading the paper except for the advice columns and Hints from Heloise because even in my horrible funk, I understood the importance of learning new ways to reuse paper napkins. (Apparently, if you refold them inside-out, no one will notice the stains, though I haven’t actually tried this myself yet.)

One day while perusing said newspaper, I happened on a “Pets for Sale “column directly below “Hints from Heloise,” and fell in love with a photo of an adorable black puppy destined to become an adorable huge dog. No matter. I desperately wanted him. I planned to name him Bernie, after Bernie Sanders and pictured happy, yes, actual Happy! jaunts through the neighborhood. Then reality set in. I was still too debilitated to tussle with a strong, frisky puppy, and didn’t have the time or money to get our yard fenced. Yet another non-starter. Back to deep sighs and moist Kleenex.

Dismal weather and more bad news exacerbated my depression. When we attended a Trivia gathering and I couldn’t come up with a single correct answer, my self-esteem, tenuous at best, plummeted. The time had come to invite Pollyanna back into my life.

“Look”, I told myself, “it’s only Trivia. You doubtless have so much useful information stored up, you just don’t have room for trivial stuff.” Hey, good for me, a baby step away from despair.

Maybe I could figure out something to lighten the household mood. I worked at cooking some tastier meals. I ordered new spices from Penzy’s. I changed the living room decor and redecorated the mantle. I even went out to see some music with my husband and discovered the song “Shut Up and Dance With Me” by Walk the Moon could provide a brief interval of upbeat-ness, which was encouraging, but I couldn’t listen to it 24 hours a day. My mood was moment-to-moment, certainly not joie de vivre, more a range between depression and Meh-de vivre. There was definitely more needed to change the dynamic.

I sensed an idea struggling to bubble up through the primordial ooze that had become my brain. When it finally burst through fully formed, I hosed it down and realized I might have found a solution. Perhaps not the most prudent or smartest plan, but maybe that wouldn’t’ matter. I’d broach it anyway. I was desperate.

“Hey, I just had this awesome idea! Kittens!”

I’m not clear on whether the stunned silence that met my announcement was due to its content or the fact that I was actually sounding cheerful.

“What about kittens?“

“Maybe we should get some kittens. You know, something to take our minds off everything else. We liked having cats before.”

“True, but those were legacy cats, not kittens. And after Maisie died, I distinctly remember you saying ‘no more pets.’”

“I know, but I was grieving. I changed my mind. I think we need something besides the news to focus on.”

“Ok,” my bemused husband nodded. “You make a good point. Kittens could keep us busy.”

And that is why we are now happily owned by two eight-month-old felines. Thistle and Bramble. I thought about naming one of them Pollyanna, but really, I didn’t want to burden a happy young cat with maudlin reminiscences of my distant past.

Honestly, they have exceeded our expectations. My mood has lightened, I feel needed, and when one bounces over for a quick pat, I am validated. My husband thinks they’re charming.

Kittens. Probably not the solution for everyone. Therapy might be less of a commitment and possibly cheaper in the long run.

But if you just need to see eager little faces or hear happy purring to raise your endorphins, it’s kittens all the way.

© 2025 Faith Ellestad

Faith has been writing to amuse her family since she was old enough to print letters to her grandparents. Now retired, she has taken the opportunity to sort through family memorabilia, discovering a wellspring of tales begging to be told, which she hopes to expand upon in written form (where appropriate, of course!). She and her husband live in Madison, Wisconsin. They are the parents of two great sons and a loving daughter-in-law, and recently expanded their family to include Thistle and Bramble, two irrepressible young felines.

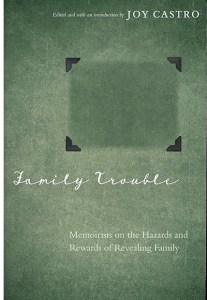

Share YOUR “Family Troubles”

For three weeks, my posts have focused on “Family Troubles”–the difficulties we encounter when we put our life stories out in the world, where people whose lives overlap ours can read them. Now I want to hear from you–have you published a memoir? How was it received by family and friends?

Write about it. Send my way–see Submission Guidelines here.

The posts in this series so far:

Your true stories, well told, are welcome here!

Share this: