by Donald A. Ranard

Photos by Ray Oram, a British volunteer who taught English with the author at the lycée.

I met the German at the night market in Chiang Mai. The northern Thai city was a small town then, and in the evening, people would gather in the open-air night market, strung with white lights, to drink Thai beer and eat khao soi noodles. I spent my days in my small rented room writing and my nights at the night market drinking beer and watching people. There was a waiter who became a waitress over a two-week period, each day adding a little more make-up and sashay, and there was an old blind man, led by a young boy, who went from table to table, blowing loud, random notes on a harmonica. You didn’t pay him to play; you paid him to stop and go away.

It was December 1975. In May, six months before, I’d been evacuated to Thailand, from Savannakhet, a small riverside town in central Laos, after the Pathet Lao communist takeover. The U.S. had spent billions over two decades in Laos, funding a corrupt government that had collapsed without resistance after the fall of Saigon in April. U.S. officials in Laos had maintained a demeanor of unflappable optimism that toward the end seemed delusional. To men who’d had their formative professional experience in World War II, defeating two of the world’s greatest military powers, the thought that the U.S. might meet its match in a poor, tiny backwater, population 3 million, had seemed inconceivable.

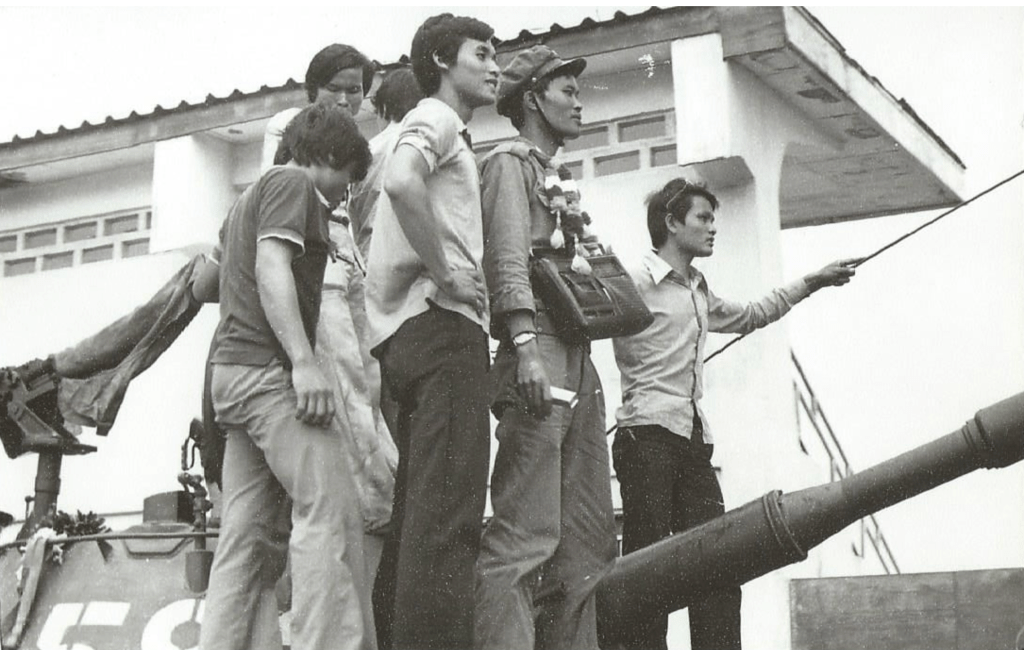

But reality could not be ignored forever. As local officials fled to Thailand, the town was taken over by pro-Pathet Lao students—some of them, my students from the French-medium lycée where I taught English as a Fulbright grantee. Along with other Americans, I was placed under house arrest. But it was house arrest Lao style, which is to say it was loose, unclear, and negotiable, and when the PL finally rolled into town in a convoy of jeeps, trucks, and an old Soviet tank, no one seemed to care that I was among the curious lining both sides of the street. The commander sat in the head vehicle, an old jeep with a flat back tire, giving the people their first look at life under the new regime: ka-plunk, ka-plunk, ka-plunk. After the jeep, came canvas-covered trucks full of soldiers in green khaki and floppy Mao-style hats. They were young—younger than my students, many of them—and behind the impassive expressions I sensed the wariness of villagers on their first trip to town. Students jumped up on the trucks and joined the soldiers, posing for friends who ran alongside taking pictures, and when I saw them, the smiling sons of the elite, in their bell-bottom trousers and Lacoste polo shirts, next to the grim soldiers in their threadbare uniforms, I felt a twinge of fear for my students. This was not the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

The next day, the small community of American aid workers and English teachers gathered at the landing strip that served as the airport. “Bon chance,” said the director of the French cultural center, an old Indochina hand, who had come to say goodbye. He seemed sincere in his sympathy, but as I shook his hand, I wondered how he really felt. Not so many years ago, the Americans had watched the French lose the First Indochina War. We had arrived on the scene confident we would succeed where the French had failed. We didn’t lose wars—we were Americans! Now we were leaving, and the French were staying.

An hour later, we stepped down from the cargo plane onto the tarmac in Udorn, Thailand, to a small scrum of waiting reporters. “End of an era,” said Sandy Stone, Savannakhet’s USAID director. “Or should I say, error?”

Stone, a retired colonel who’d served in World War II in Europe with OSS, the forerunner of the CIA, was in his late 50s then and young enough for one more overseas assignment: Afghanistan.

#

The German and his young American friend were sitting at the table next to me, and I fell into a conversation with them the way you do with fellow foreigners abroad. The German was an affable old Thai hand in his late forties. His young American companion was a freelance photographer, quiet and intense, new to journalism and the region.

They’d returned a few days before from Ban Vinai, a makeshift camp in northeastern Thailand, near the Laotian border, built in great haste to accommodate Hmong refugees pouring into Thailand. After the easy-going lowland Lao had proven to be unenthusiastic fighters, the CIA had recruited the Hmong hilltribe people to fight in what the agency touted as a “low-cost” war—low cost, that is, in American lives. For the hill tribe people, the cost had been grievous; the war had killed, injured, or displaced nearly half of the Hmong in Laos. In the end, boys as young as ten were pressed into military service. There was an informal rule, a CIA operative would later recall: A boy had to be as tall as an M-1 rifle to become a soldier.

The Hmong had been promised they’d be taken care of if things ended badly. When things did end badly—and more quickly than anyone had anticipated—only the leaders and their families were evacuated to Thailand. Now thousands of men, women, and children were making the long dangerous journey on foot from the mountains of Laos and across the heavily patrolled Mekong River to Thailand, many dying along the along the way. Soon Ban Vinai refugee camp would become the largest Hmong community in the world.

#

“Well, there’s one good thing about all this,” the American photographer said. “The U.S. will think twice the next time their government tries to drag us into a war.”

The German regarded his young friend with a small smile. “You’d be surprised what people will allow their government to do when they’re angry and afraid,” he said quietly.

A few days later I left Thailand on a backpacking trip through India and Nepal, and I never saw them again. But a little more than a quarter-century later, in a feverish run-up to another ill-conceived war with disastrous consequences, I remembered the German and what he said in the night market in Chiang Mai.

© 2025 Donald A. Ranard

A somewhat different version of this essay first appeared in So It Goes, a literary magazine published by the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library.

After his evacuation from Laos, Donald A. Ranard worked in refugee assistance programs in Southeast Asia and the U.S. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Los Angeles Times, New World Writing Quarterly, The Best Travel Writing, and elsewhere. In 2022, his flash fiction story “5/25/22” was longlisted by Wigleaf as one of the year’s top 50 Very Short Fictions, and his play, ELBOW. APPLE. CARPET. SADDLE. BUBBLE., about a wounded Iraq war veteran, placed second in a national playwriting contest.

Perfect mood, moving between the night market to Laos and back again. I taught English to Lao and then Hmong (Khmer too) in Wisconsin soon after the fall of Laos and Cambodia. You gave a clear, concise picture of the geopolitical situation, while keeping the tone of a short story. The optimist vs the war-weary pessimist makes for a haunting but true to the bone ending.

The Hmong sure got screwed. And now one from Minnesota (arriving here at age 2) has been deported. The screwing continues.

LikeLike

Perfect mood, moving between the night market to Laos and back again. I taught English to Lao and then Hmong (Khmer too) in Wisconsin soon after the fall of Laos and Cambodia. You gave a clear, concise picture of the geopolitical situation, while keeping the tone of a short story. The optimist vs the war-weary pessimist makes for a haunting but true to the bone ending.

The Hmong sure got screwed. And now one from Minnesota (arriving here at age 2) has been deported. The screwing continues.

LikeLike