By Sarah White

To download Bruno’s pizza recipe, see link at end of story.

About travel, T.S. Eliot famously wrote, “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

I would add that we hope to arrive better than when we left—to have learned something, realized something, or simply become energized. For my husband Jim, that hope was realized in Italy last spring, and the beneficiary was our regular Thursday night pizza.

In March, 2025 I enrolled in a language school in Ascoli Piceno for a two-week course. My husband Jim, while not motivated to study the language, did enroll in the extracurricular activities offered, which included visits to historical and cultural sites and several cooking lessons. One evening, an activity took us to a pizzeria, Da Bruno’s, located right around the corner from the palazzo that housed both the language school and the apartment we rented from it.

Jim—a retired chef—has been making pizza ever since grade school, when on Friday nights he’d stay up late watching horror films and making pizza from a box mix. He now cooks from ingredients, not a box, and his methods have shifted over time—rolling pins, hand-tossing, back to rolling again—but the result, to his taste, was never quite right.

We met up with our classmates at Da Bruno’s an hour before the restaurant’s opening time of 7pm. I expected a demonstration kitchen. Instead, the seven of us crowded into a hallway and craned our necks through a doorway into the tiniest kitchen I’d ever seen.

Bruno worked methodically in the cramped space, his hands dropping already-prepared balls of dough into a machine that flattened them into disks that he then stretched by hand. An assistant behind him prepared toppings. In the hallway, we took turns at the doorway, thrusting our phones into the room to capture photos of Bruno pivoting, hands flying between trays of dough, his work surface, and the mouth of the oven into which he slid his loaded peel. An eighth body joined us in the hallway—young Tahar from Turkey, the language school’s social media intern. His job was to document the rest of us receiving our pizza lesson. As Bruno worked, he explained what he was doing. Tahar filmed video. Jim hung back from the scrum. “I felt like I didn’t really need to be there, so I was fine on the side, half listening,” he said.

Bruno’s peel disappeared again and again into the half-round oven door, each time with a dough circle bearing a different assortment of toppings. Bright aromas of garlic, tomato, and onion wafted around us. A darker must bloomed in the air—Bruno grating a knob of black truffle as big as a child’s fist over one of the pies.

We took note of Bruno’s artistry. Some pies were very spare with just truffle, parmesan, and coarse salt and pepper; others, judiciously topped with meats and cheeses.

Once Bruno had assembled six or seven pizzas under our gaze, he paused to scribble his formula in metric units on a sheet of graph paper. We students dutifully leaned in to photograph the page. Bruno told us he uses only hard flour from Alberta, Canada. The other ingredients were water, oil, and a bit of sugar and salt.

Then came the moment that mattered: Bruno said, “L’impasto dev’essere morbido e liscio come il sederino di un bambino —The dough must be soft and smooth, like a baby’s bottom.”

After an hour of watching Bruno, we gathered with our classmates at a long table and enjoyed the fruits of his labor, ending with a pie folded over calzone style, filled with Nutella, dusted with powdered sugar, and served in thin strips. Each crust was uniformly thin but stood up to the task of supporting whatever topping it carried. Each was delicious.

For Jim, da Bruno’s pizza lesson was a revelation.

“I’ve been disappointed with my pizzas for a while,” he admitted. “So firm that it had to be rolled out, although I went through a period of hand tossing, then back to rolling. I wanted a thin crust, but it either got too thin in the middle or burned at the edges. It just wasn’t what I wanted.” I found this admission surprising. We had shared countless pizzas together in our forty-plus years of marriage, and to me, they were fine. Amazing, even. But for Jim, no.

Softness was the missing piece. With enough water in the mix, the dough could be stretched instead of rolled. That made for a better crust in a number of ways. The softer dough rose more, giving it a more bread-like tooth. While hand-tossing is dramatic, the centrifugal action thins out the center, leaving it vulnerable to leaks and tears. Stretching instead creates a solid center ringed by a ridge that keeps the sauce contained and yields a classic, browned border.

Back home, Jim had me pull up the photo of the recipe. He converted the measurements, adjusted down to what seemed right for one pizza, and gave it a try. He nearly reached for the rolling pin, then stopped himself. “This dough is soft enough,” he said. “I should just try stretching it.”

He pressed the dough flat, then used the edge of his hand to push it outward. One hand anchored, the other nudged and turned the circle of dough. Gradually, it grew thinner and rounder. There were uneven spots at first—holes even—but his technique quickly improved.

“By the third try, I was getting a decent crust,” Jim said.

The changes didn’t stop there. The class had impressed on him the balance of Italian pizzas—restrained toppings, flavors that left space for the crust to shine.

“I quit using canned pizza sauce,” Jim told me. “Now it’s just fresh tomatoes, oregano, garlic, and a pinch of pepper flakes.”

He also cut back the cheese. Once, he would have spread eight ounces across a twelve-inch round. Now he stops at six. “You can taste everything better this way,” he said. “It’s lighter. More balanced.”

Watching him refine his method, I thought again about Eliot’s line. Travel changes us most when it sends us back to what we already know, with fresh eyes. Jim had been a pizza-maker for decades. All it took was one phrase in a crowded Italian kitchen to unlock the crust he had been searching for all along.

The secret wasn’t a wood-fired oven, imported flour, or exotic toppings. It was softness. Simplicity. A willingness to stretch, rather than force.

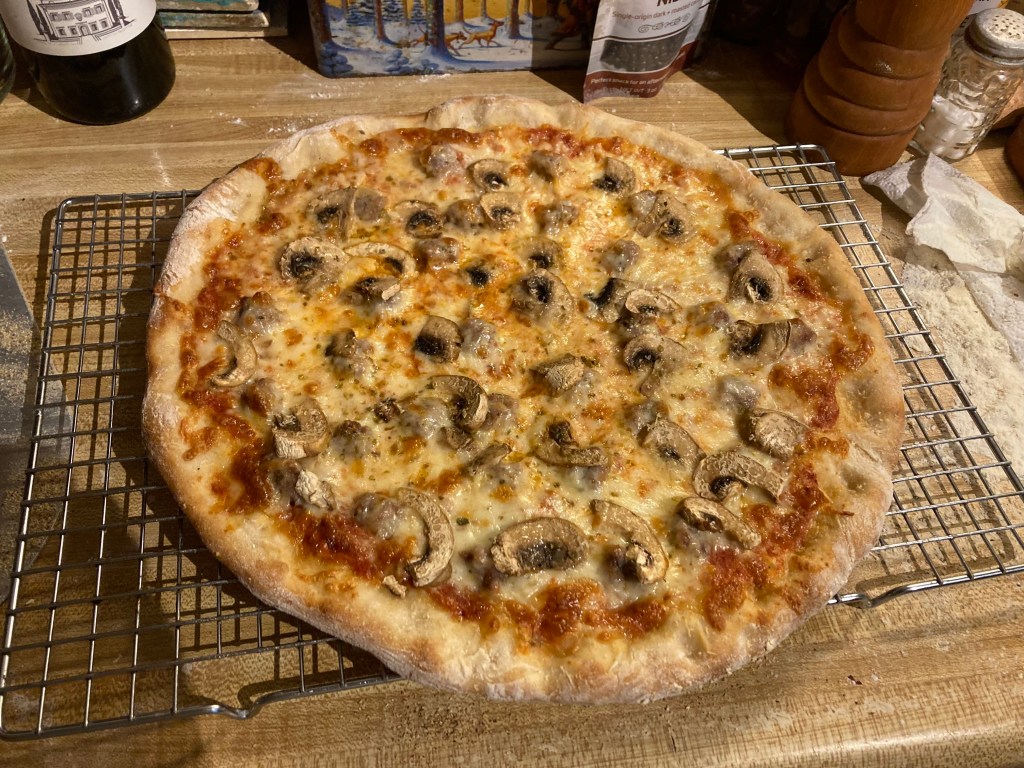

Now, on Thursday nights, our kitchen counter holds a ball of dough resting under a towel. Jim works it with the edge of his hand, turning, stretching, coaxing it wider. Fresh crushed tomatoes sit nearby. Grated mozzarella waits in a small bowl, not an overflowing mound.

I watch him assemble the pizza, place it in the oven, and bring it out with a proud grin. The crust is thin and crisp, the flavors bright.

Our pizza nights are better than ever.

© 2025 Sarah White

Dear Sarah:

I hope things are well with you and Jim.

I enjoyed reading your story and how Jim’s skills in making pizza have changed and improved. Great photos! I’m hungry. Thanks for sharing.

Carol J. Blatter

LikeLike

That was delicious!

LikeLike